US vs Nigeria: Is It All About Alleged “Genocide”?

Authors: Yusuf Musa & Prof. Jabir Musa

Introduction

The relationship between the United States and Nigeria has long been shaped by a combination of strategic interests, democratic advocacy, and security concerns. Yet in recent years, the bilateral discourse has increasingly gravitated toward allegations of “genocide” in certain regions of Nigeria, particularly the Middle Belt and parts of the North. These allegations evoke strong moral and legal implications under international law and have become central to debates in diplomacy, media narratives, and public opinion.

At first glance, these allegations appear to focus purely on human rights violations and the protection of vulnerable communities. However, a deeper examination reveals that the situation is far more nuanced, shaped by historical, socio-political, economic, and geopolitical factors. This essay explores the multiple dimensions of the US-Nigeria discourse on alleged genocide, situating it within both domestic realities and international politics. The aim is to offer a clear, unambiguous analysis in the Centre For Contemporary Studies (CCS) style, blending narrative flow with analytical depth, illustrative examples, and reflective insight. By unpacking the interplay between perception, narrative, and policy, we seek to provide a comprehensive understanding of whether the tensions between the US and Nigeria are truly about genocide, or if broader interests are at play.

Historical and Political Context

Nigeria’s post-independence history is shaped by a complex interplay of ethno-religious diversity, colonial legacies, and competing visions of nationhood. The Biafra war (1967–1970) is widely regarded as a seminal event that continues to influence both domestic and international perspectives on Nigerian conflict. During this period, narratives of mass killings and starvation entered the global conscience, shaping the lens through which external actors often view Nigeria’s internal conflicts.

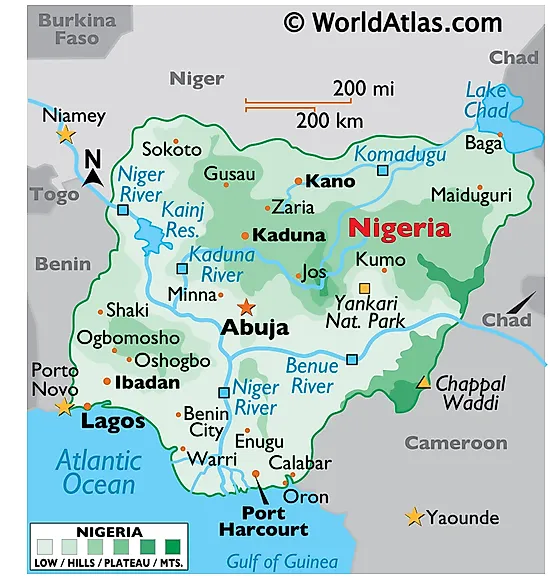

In the decades since, Nigeria has experienced numerous forms of violence, from Boko Haram insurgency in the North East to communal conflicts in the Middle Belt and persistent banditry in the North West. Each of these has contributed to a perception, both domestically and abroad, of insecurity, targeted attacks, and human suffering. Yet, while the scale of violence is undeniable, attributing it uniformly to genocidal intent oversimplifies a far more complex reality. Understanding Nigeria’s internal security challenges requires appreciating historical grievances, resource competition, and socio-economic disparities. Certain communities feel marginalized politically and economically, and these feelings have historically fueled cycles of violence. It is within this context that foreign governments, including the United States, sometimes frame local conflicts in terms of alleged genocide.

Alleged Genocide: Definition and Application

Legally, genocide is defined by the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The definition is precise: it requires the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group through acts such as killing, causing serious bodily or mental harm, inflicting destructive conditions of life, or imposing measures to prevent births.

In Nigeria, allegations of genocide often focus on ethno-religious conflicts in the Middle Belt and Southern Kaduna. While reports of violence, displacement, and massacres are deeply concerning, the critical question is whether these acts constitute a deliberate, systematic attempt to destroy specific groups. In most cases, evidence points to localized, complex, and reactive violence rather than centrally orchestrated genocidal campaigns.

The politics of labeling cannot be ignored. Historically, states and international actors have invoked “genocide” selectively, often in alignment with strategic or humanitarian objectives. Rwanda in 1994, Darfur between 2003 and 2008, and Tigray in Ethiopia in the 2020s illustrate how the term can simultaneously mobilize moral outrage and serve political ends. In the Nigerian context, allegations sometimes reflect diaspora advocacy, foreign policy considerations, and media amplification rather than strictly legal determinations.

US-Nigeria Relations: Strategic and Moral Dimensions

US-Nigeria relations encompass multiple dimensions: security cooperation, economic engagement, democratic advocacy, and regional stability. Nigeria’s demographic weight, economic potential, and geopolitical influence make it a crucial partner for the United States. Counterterrorism efforts against Boko Haram and ISWAP, peacekeeping contributions in West Africa, and partnerships in trade and investment illustrate the strategic stakes.

When the United States raises concerns about alleged human rights violations or genocide, these concerns are filtered through several lenses. Highlighting alleged atrocities increases moral pressure on the Nigerian government to adopt reforms or change policies. US policymakers respond to advocacy groups, religious organizations, and media narratives that amplify human rights concerns. Presenting itself as a defender of human rights bolsters the US’s credibility in other regions and enhances its soft power.

This multi-layered interplay suggests that allegations of genocide serve not only humanitarian purposes but also strategic and political objectives. They are as much about perception and influence as they are about factual realities on the ground.

Domestic Reality versus External Perception

A nuanced understanding of Nigeria’s internal conflicts is critical. Violence in Southern Kaduna, Plateau, Borno, and other regions often stems from a combination of historical grievances, economic pressures, and environmental challenges. Scarcity of land, water, and grazing areas has increasingly led to farmer-herder clashes. Communities that feel politically or economically marginalized may engage in or become victims of violence. Inadequate policing, judicial gaps, and insufficient local governance further exacerbate insecurity.

While these dynamics produce devastating human consequences, they do not necessarily constitute genocide in the strict legal sense. Nevertheless, external narratives often simplify the situation, presenting selective incidents as evidence of systemic intent to exterminate certain groups.

Media Narratives and Advocacy

Media and advocacy groups play an outsized role in shaping perceptions abroad. Diaspora organizations, religious networks, and social media amplification can distort the scale or nature of conflicts. Headlines invoking “genocide” resonate globally, generating moral outrage and potential policy action.

However, selective use of such terminology risks politicizing tragedy, undermining dialogue, and weakening local ownership of solutions. A CCS-style perspective emphasizes interrogation of narrative, perception, and consequence. Responsible framing is as important as highlighting human suffering, for both constructive engagement and international credibility.

Economic and Geopolitical Dimensions

Nigeria’s abundant natural resources—oil, gas, minerals, and fertile land—are central to domestic stability and international attention. Historically, resource-rich regions have attracted external intervention framed under humanitarian rhetoric. In Congo from the 1960s to the 1990s, resource conflicts were interpreted through Cold War ideological lenses. Libya in 2011 saw humanitarian intervention intertwined with oil and strategic interests.

In Nigeria, allegations of genocide sometimes intersect with resource considerations, raising questions about timing, emphasis, and selectivity. While this does not diminish the reality of human suffering, it underscores the complex motivations behind international interventions and commentary.

Legal and Diplomatic Implications

The label “genocide” carries profound legal weight. Recognition by international bodies obliges action under the UN Genocide Convention, including potential sanctions, interventions, or international prosecutions. For Nigeria, this raises legitimate sovereignty concerns, as external intervention based on allegations can threaten domestic governance, complicate reconciliation efforts, and impact foreign relations.

Diplomatically, Nigeria has countered by emphasizing the complexity of internal conflicts, the multiplicity of causal factors beyond simple ethnic targeting, and efforts to implement security reforms and support affected communities. Yet global audiences often remain swayed by emotive narratives that prioritize moral outrage over analytic precision. This misalignment highlights the delicate balance between sovereignty and global accountability.

Case Studies:

Global Parallels

Examining historical parallels provides insight into the dynamics of alleged genocide and international response. Rwanda in 1994 saw international inaction result in nearly one million deaths, shaping future norms around the “responsibility to protect.” In Darfur between 2003 and 2008, alleged genocide framed sanctions and humanitarian operations, with contested narratives on both intent and scale. In Tigray, Ethiopia during the 2020s, competing narratives illustrate how labeling conflicts can simultaneously mobilize intervention and exacerbate international tensions. These cases underscore the dual edge of the genocide label: it can catalyze humanitarian action while simultaneously complicating diplomatic relations and internal conflict resolution.

Social Cohesion and National Response

Within Nigeria, the discourse on alleged genocide carries tangible consequences for national unity. Ethno-religious communities may feel targeted or ignored depending on how violence is framed internationally. Constructive responses include strengthening local conflict resolution mechanisms, ensuring equitable economic and political representation, and enhancing security presence, judicial enforcement, and accountability. From a CCS perspective, measured, evidence-based engagement is paramount. Reactive or emotive narratives may inflame tensions rather than resolve them, undermining both human security and governance.

Beyond Allegation:

A Multi-Dimensional Analysis

Ultimately, tensions between the US and Nigeria over alleged genocide cannot be reduced to a single cause. Multiple factors converge. Human rights concerns reflect the undeniable suffering and displacement of communities. Geopolitical strategy shapes the US’s framing and actions regarding Nigeria. Media amplification influences perceptions and policy agendas, while domestic governance challenges, including state capacity, historical grievances, and socio-economic disparities, drive conflict dynamics.

A CCS-style assessment emphasizes clarity, evidence, and contextual understanding. Allegations of genocide are neither entirely fabricated nor wholly uncontested; rather, they are part of a complex matrix of local realities and global narratives.

Recommendations for Constructive

Engagement

Nigeria’s path forward involves rigorous internal documentation to provide credible evidence for international engagement, proactive governance that strengthens local institutions and addresses root causes of conflict, and inclusive development that reduces marginalization and resentment. Transparent communication with the United States and other international actors can prevent misperceptions and reduce friction.

Global actors, in turn, have a responsibility to distinguish between human rights violations and legally defined genocide. Interventions should be evidence-based and avoid reactionary policies driven solely by emotive narratives. Support for local solutions, including capacity-building, conflict resolution, and governance reforms, is far more effective than imposing external agendas that may unintentionally exacerbate tensions.

Conclusion

The US-Nigeria discourse on alleged genocide is multi-layered, encompassing genuine human rights concerns, strategic calculations, economic interests, and media dynamics. While human suffering in Nigeria is real and demands attention, labeling conflicts as “genocide” often simplifies complex socio-political realities. In assessing the situation, it is essential to balance moral imperatives with evidence, recognize historical and structural drivers of conflict, and navigate the interplay of domestic sovereignty and international scrutiny. Allegations of genocide are partly about human rights, partly about geopolitical positioning, and partly about the power of narrative in shaping global perception.

From a CCS perspective, clarity, context, and analytical rigor are critical. For Nigeria, the task is to strengthen governance, address root causes of conflict, and engage internationally with confidence and transparency. For the United States and global observers, the challenge is to engage responsibly, acknowledging suffering without distorting context or politicizing tragedy. Only through nuanced, multi-dimensional analysis can the discourse move beyond accusation to constructive action, ensuring that moral concern, strategic interest, and local realities converge toward sustainable peace and security.

Authors:

Yusuf Musa – CEO, Centre For Contemporary Studies

46, Ramat Road, Kaduna, Nigeria

Prof. Jabir Musa – Senior Fellow, Centre For Contemporary Studies

(Foreign Relations Desk)