Hausa Intellectualism from the 17th Century

Professor Abdullah Uba Adamu

For the last two or so months, I have been involved in a frenzy of writing with a tight deadline, fortified only by continuous, albeit tiny, cups of my favorite Turkish coffee. On the surface, the task seemed fairly straightforward – the editor even wrote informing us (about 35 writers) that we can “warm up” our previous writings. I refused to do that, insisting on discarding everything I have done in the area and coming up with something different, principally so that I can learn something new.

The task I was assigned was to write two chapters. The first was Early Hausa Literature, while the second was The Ajami Script in Africa. Seems fairly straightforward, right? The devil is in the details.

The task on Early Hausa Literature focuses on Hausa literature BEFORE 1900, and definitely before British colonial occupation, and with focus on 17th century. Ibrahim Yaro Yahaya’s “Hausa a Rubuce: Tarihin Rubuce Rubuce Cikin Hausa” [Hausa in Writing: the History of Writing in Hausa] is a good starting point, but not enough. So I had to dig deeper than deep, because beside just the title, the editors want a bibliographic listing of the major works by Hausa or in Hausa. I went as far back as 1470 or so in Kano, before jumping up to 1660s in the intellectual hubris of northern Nigeria, Katsina, where I engaged with Dan Marina and Dan Masani. Islam and History of Learning in Katsina, which I co-edited with Prof. Isma’ila Tsiga became a refresher reading in the new task.

After gallons of coffee, and sleepless nights, I have learnt a lot – about the Hausa, about scholarship and about Hausa intellectualism. Here is a quotation from one of the most respected authorities on early Hausa intellectuals written in 1901.

“On first proceeding to West Africa (the Gold Coast), and on commencing a study of the Hausa language, the compiler of this work was struck by the comparatively high standard of education found among the Hausa MALAMAI or scribes. Arabic characters are used by them, as by the Swahili of East and Central Africa; but, whereas any natives met with there possessed but a very superficial knowledge of the Arabic language or writing, the Hausas could boast of a legal, historical, and religious literature, which was to be found preserved by manuscripts. The MALAMAI were everywhere the most respected and honoured members of the community. It was disappointing, however, at any rate for one who wished to study Hausa, to find that ali their manuscripts were written not only in Arabic characters, but also in that language. This appears to be universally the case, even in Nigeria. The use of Arabic today among the educated Hausas corresponds to that of French and Latin in England in the middle ages.”

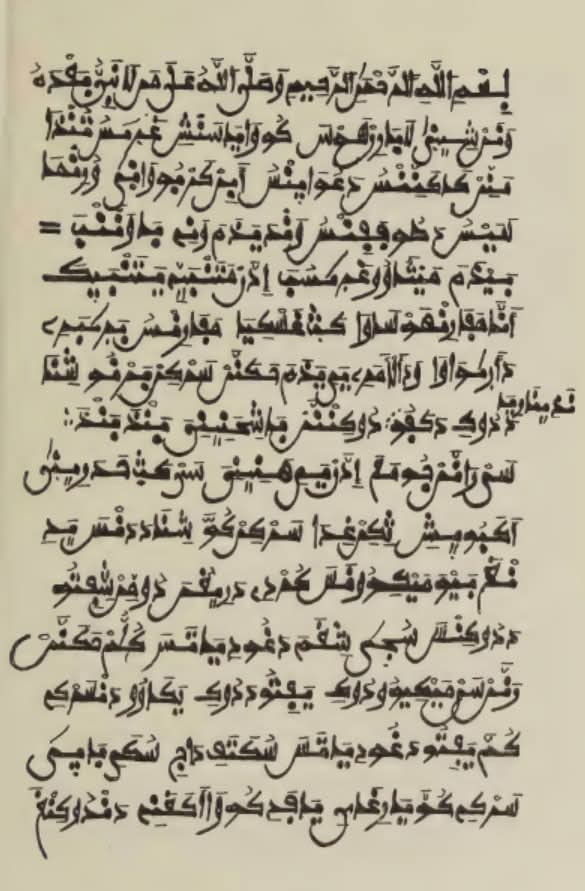

This was from the author’s note by Rattray in his collection of Hausa Ajami folk-tales published in 1913, although he wrote the author’s note in 1911. Looking at Hausa scholarship from 1660s to about 1890 is revealing. Rattray’s book is just of quite a few. Rattray’s collection contains a history of the Hausa people, based on folkloric perspective written in incredible Hausa Ajami. I have included the first page of the manuscript. Marvel at the incredible penmanship.

And yet, a distinct people with this legacy stretching back centuries are being relegated to a mere language, a fallacious assumption (“Hausa ba ƙabila ne ba, harshe ne”). Now I can confirm the historical origin of this rubbish. It was al-Ḥasan ibn Muḥammad al-Wazzān al-Fāsī, commonly called Leo Africanus. His The History and Description of Africa, published in 1526 after a casual visit to north Africa distorted a lot of history of Hausaland which he never visited.

Then there is “Hausa Prose Writings in Ajami by Alhaji Umaru” from A. Mischlich, H. Sölken's collection and edited by Stanisław Piłaszewicz of the University of Warsaw. It is a significant collection featuring various documents written in Hausa Ajami script. This compilation preserves historical narratives, religious texts, and cultural expressions in Hausa society, offering insights into local perspectives on literature and Islamic scholarship. The texts reflect a blend of Hausa oral tradition with Islamic literary traditions, making them valuable for understanding the cultural and religious dynamics in the region in the late 19th century.

Imam Umaru, who lived between 1858 and 30 June 1934 was from Kano, and settled in Kete‑Krachi, Ghana in the 1896. His appointment and settlement in Krachi mark a significant period where he produced many of the Hausa Ajami and Arabic writings that were later preserved and studied by European scholars such as Gottlieb Krause and Stanislaw Piłaszewicz.

Imam Umaru was a towering intellectual and cultural bridge—a committed Islamic scholar, prolific Ajami writer, respected imam, and mediating figure during colonial transitions whose body of work continues to inform our understanding of Hausa and West African history. The current collection contains 11 histographies of various communities from Kano, to Zamfara, Katsina, Dagomba, Macina and Burkina Faso. All in Hausa Ajami. I am lucky to actually own the book which I bought for 74€ on a trip to Germany.

I will leave you with Prof. Umar B. Ahmed’s fascinating translation of German Rudolf Prietze’s massive collection of Hausa Ajami works, “The Hausa World of Rudolf Prietze: Being the Complete Collection of the Scholar in the Hausa and German Originals and the English Versions, 2 vols.” Ahmadu Bello University Press. It contains 2,052 pages. It’s described as the complete collection of Prietze’s works in the original Hausa and German, alongside English translations. Contains stories and plays. One of the plays I particularly like is “Yan Matan Gaya”r related to Prietze by obviously a Gaya indigen in Tunis in late 19th century. The two volumes are available at Arewa Hausa Kaduna, last time I checked.

The Hausa. People, not language. Travelers. Merchants. Adventurers. Intellectuals. Duniya!