Language, Culture and Identity | Developments of Hausa Syllabary

Part 1 – Syllabaries, Scripts and National Identities

Professor Abdallah Uba Adamu

On 20th June 2025 FIM Magazine (online) reported the presentation of a new Hausa Syllabary, ASALI by Dr. Korao Hamadou from the Republic of Niger. Facing attendees at the conference—including language experts—Dr. Hamadou presented what he created and imagined to be a new Hausa syllabary. An intense question and answer session followed, but Dr. Hamadou was not ready to unveil his new syllabary yet, and asks for patience till the proper time. But, first, what is syllabary?

A syllabary is a writing system where each symbol (or character) represents a syllable, which is a unit of pronunciation consisting of a vowel sound, or a vowel and one or more consonants. It's a way to represent language in writing where the syllable, rather than individual sounds (like letters in an alphabet), is the basic unit. To cut through the morass in Hausa, you could say that “syllabary na nufin ƙirƙiro da haruffan da za su wakilci wani harshe, yadda su waɗannan sababbin haruffan ba su da alaƙa da haruffan Larabci ko kuma Latinanci, watau haruffan boko.”

Examples of syllabaries include Japanese Kana (Hiragana and Katakana), Yi Syllabary (China), Cree and Ojibwe Syllabics (Canada). In West Africa, common syllabaries included N'Ko (Mande languages) and Vai (Liberia, Sierra Leone). Tifinagh (Tuareg) may look like a syllabary, but it is not; it is an alphabet (consonant-vowel script). In northern Nigeria, the first Hausa syllabary was created by Eng. Musa Abdullahi in 1988. But I will focus on him in Part 2. In this first part, I want to explain what Syllabary is and how it is linked to national identity. I divided the post into parts to make it easier to read, as some complained my postings tended to be too lengthy!

The first known syllabary in West Africa is the Vai syllabary, developed around 1833 in Liberia by Mɔmɔlu Duwalu Bukɛlɛ. He reportedly conceived the idea in a dream, where a tall, dignified white man in a long coat appeared and told him, “I am sent to you by other white men … I bring you a book.” In the dream, Bukɛlɛ was shown numerous symbols. Although he couldn’t recall them upon waking, he later collaborated with friends to invent new ones for the Vai language. In 1854, the German philologist S. W. Koelle met Bukɛlɛ while conducting research on the Vai language and documented this account.

An alternative theory suggests that the Vai syllabary may have been influenced by the Cherokee syllabary. The Cherokee are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. They are the largest Native American tribe in the United States today. Some Cherokee emigrated to West Africa in the early 1800s, and one of them—Austin Curtis—married into a prominent Vai family and eventually became a Vai chief. It is speculated that he may have played a role in the development of the writing system.

The Vai syllabary gained widespread acceptance among the Vai people, and by the late 19th century, it was in common use. In 1962, the University of Liberia’s Standardization Committee formalized the script. A translation of the New Testament in the Vai script was published in 2003.

Another indigenous African script is the N’ko which is not a syllabary. The N'Ko alphabet was invented by Soulemayne Kante of Kankan, Guinea, in 1949. It is mainly used by speakers of Maninka, Bambara, Dyula and their dialects in Guinea, Côte d'Ivoire and Mali.

Soulemayne Kante was born in 1922. As a young man, he was angered when he read that some foreigners considered Africans cultureless since they didn't have an indigenous writing system. In response, he developed N’ko to give African people their own alphabet to record their cultures and histories in their native languages. He wrote hundreds of educational materials in Maninka using the N'ko alphabet. His aim was to explain complex or foreign ideas to speakers of Maninka using their own language. He wrote introductory books on subjects as diverse as astrology, economics, history and religion. Publications in the N'Ko alphabet include the Qur'an, textbooks on various subjects, poetry, philosophical works, a dictionary and a number of local newspapers.

Unlike many of the other African scripts before it, N'Ko is a fully-fledged alphabet with a very distinct appearance, consisting of an eclectic mix of simple geometric shapes, angles and the occasional loop attached to a baseline running from the right to the left with letters that flow into one another, much like Arabic. The number of those who are literate in N'ko has increased without government intervention or support during the colonial and independence periods and without official support from the Islamic religious community. N'ko spread at the grassroots level because it met practical needs and enabled speakers of Mande languages to take pride in their cultural heritage,

These syllabaries and scripts represent significant efforts to preserve and promote African languages and cultures through writing systems that reflect local phonetics and linguistic structures. They contribute to linguistic diversity and cultural heritage in West Africa. They are reaffirmation of identities.

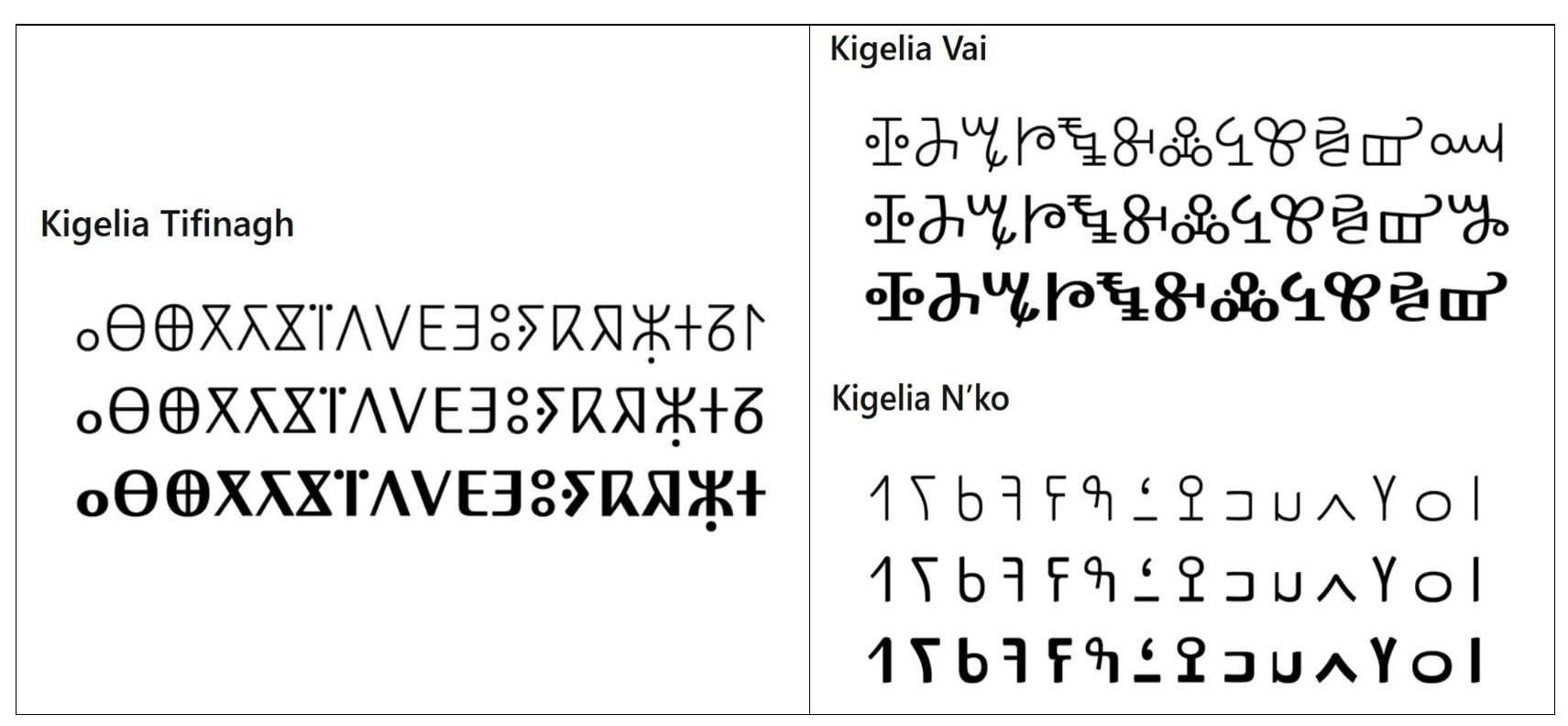

The acceptance of these scripts is so universal that Microsoft Corp. has produced a family of fonts that include these scripts as Kigelia N’ko, Kigelia Vai, Kigelia Tifinagh. This makes it easier to use the languages in modern communication. Here is the drawing of the font scripts from the Kigelia font.

Next, the first Hausa syllabary from Katsina in 1988.